Top arguments used by sophists and midwits

It's tiresome.

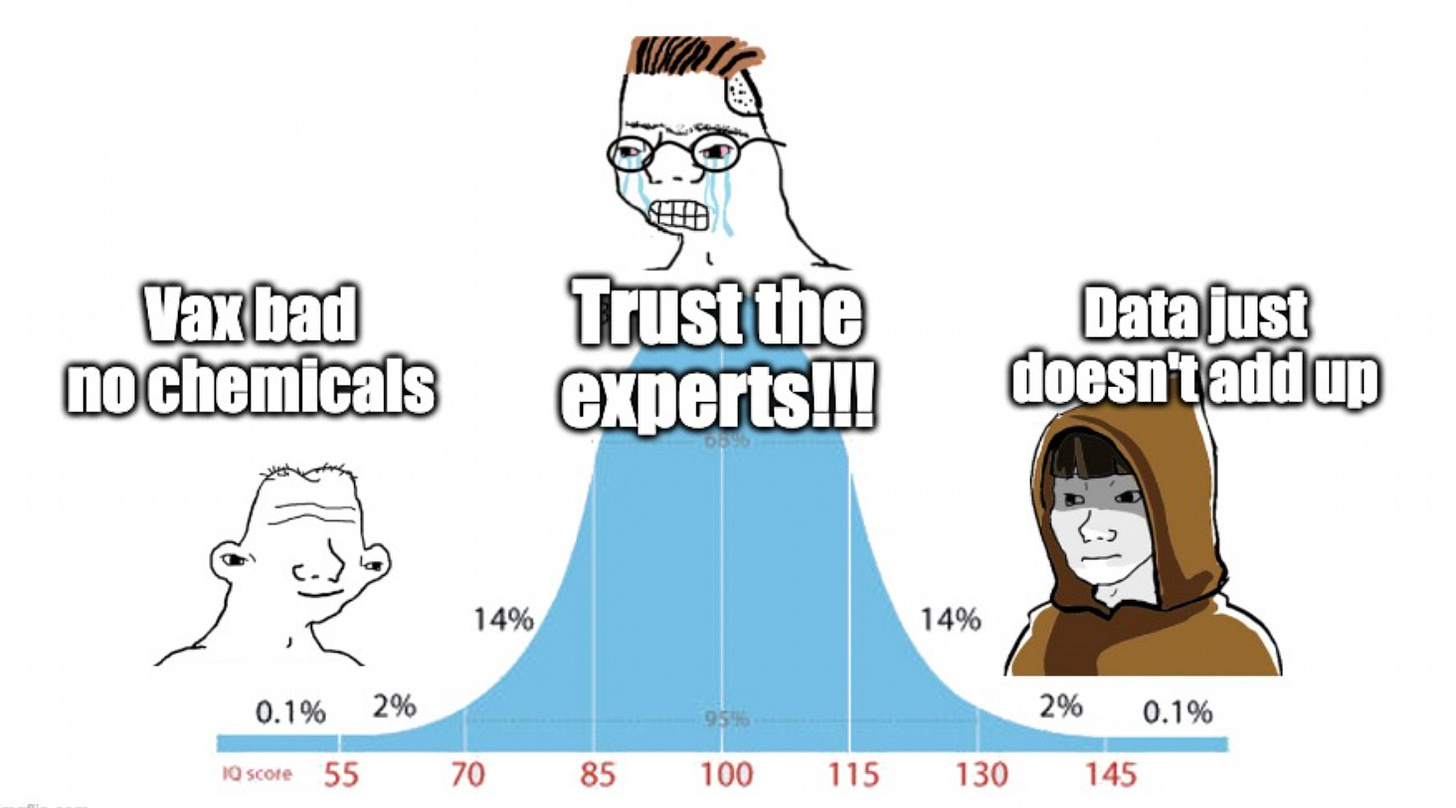

Sophistry & Midwittery

Sophists are those who engage in superficially plausible but fallacious methods of reasoning or argumentation.

Midwits are closely related to sophists. In fact, you’ll often find a sophist and midwit in the same person.

Midwits are those with middling intellect, who often get distracted from the truth by focusing on minutiae. In this article about midwits, they are described as follows:

The midwit is incapable of drawing on multiple streams of information, from many different domains, to understand the novel information in the broader context of a system.

To compensate, the midwit turns inward, focusing with increasing resolution and detail into the confines of the information itself. To the midwit, this is nuance. To the genius, he is missing the forest for the trees.

Both sophists and midwits are intelligent enough to have picked up on some of the “lingo” of science. They often have statistical-sounding things to say. This may fool you into thinking that their arguments are sophisticated, but some digging reveals that they are, frankly, full of shit.

Let’s go through some of the top phrases and arguments that sophists and midwits regularly use and abuse, so you can watch out for them.

1. “Scientific fact is reached by consensus”

This statement is usually used to shoot down scientists that have inconvenient beliefs. It serves to relegate heretical scientists to deep, dark corners where no one will hear from them again.

It’s also a tell-tale sign that you’re dealing with a sophist or midwit.

Variations of this statement include:

Scientific truth is reached by consensus

Scientific facts are what the majority of scientists agree upon

Related phrases include:

Trust The Science

It’s Established Fact

The Science is settled

The consensus can be wrong

Let’s first agree that “truth” exists independently of who or how many people believe in it.

It therefore stands to reason that it’s possible for the majority of people, even scientists, to be wrong about something, even within their own field. Thus a statement may be wrong even if everybody believes in it, and it may be true even if everybody thinks that it’s ridiculous.

That’s not to say that we shouldn’t hear what the “consensus science” has to say. But it cannot be relied upon. Scientists, like everyone else, are susceptible to delusion, peer pressure, groupthink, careerism, and corruption. The history of science is littered with examples where the majority of scientists were wrong about something, even in their own field.

Here’s a site that lists scientists whose ideas were ridiculed, rejected, or ignored at the time, sometimes for decades, before they were widely recognized. Many of them were considered “fringe” at the time.

The one issue I have with that website is that they say these maverick/heretic scientists were later “proven” correct. I’d rather say that these scientist’s theories became widely accepted or “mainstream,” because proof is a very high bar. I’m open to the possibility that even some of these “textbook” cases that are now mainstream, where “everybody knows” them to be true, could later get “overturned.”

I like what physicist Richard Feynman had to say about this:

Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts.

And:

It is necessary to teach both to accept and reject the past with a kind of balance that takes considerable skill. Science alone of all the subjects contains within itself the lesson of the danger of belief in the infallibility of the greatest teachers of the preceding generation.

Feynman describes judgement in science as the skill to “pass on the accumulated wisdom, plus the wisdom that it might not be wisdom.”

Scientists are human and science can be corrupted

We should never underestimate the capacity of humans, including our most highly credentialed scientists and doctors, to participate in mass delusion or groupthink. They are not immune to the kind of peer pressure that closes the mind to even countenancing certain ideas.

One could even argue that they might be more susceptible to this kind of pressure than the average person, because academia and medicine might select for people who care about social standing and respectability.

The situation becomes even more fraught when we consider the fact that science in the 21st century has increasingly come under the influence of money, bureaucracies, corporations, and other parties that are far from disinterested truth seekers (see this and this). This institutionalized Big Science, has created pockets of “knowledge monopolies,” or research cartels that serve to exclude dissident views.

In the end, you can’t rely on “consensus” for the truth. It’s a scary thought for some, but sometimes our society’s most credentialed people, the so-called experts, get things spectacularly wrong.

2. “But it’s not peer-reviewed”

Variations of this statement include:

It’s just a preprint.

That’s not from a reputable journal.

This is one I hear a lot. The sophist or midwit saying this will only accept data from peer-reviewed literature. They forget that most of science was done before the widespread adoption of any formalized “peer review.”

Hear what ecologist Allan Savory had to say about this:

I highly recommend you listen to the whole clip, which is under two minutes, but here are some quotes from it:

People are coming out of the university with a master’s degree or a PhD, you take them out into the field and they literally don’t believe anything unless it’s a peer reviewed paper. That’s the only thing they’ll accept… That’s their view of science.

Going into universities as bright young people, they come out of it brain dead, not even knowing what science means. They think it means peer-reviewed papers, etc.

No! That’s academia.

It’s not that peer review is useless. When peer review is done well, it can be extremely useful. It’s just that some people have this idealized notion of it; that it filters for the “best science,” most of the time.

Here’s a description of how peer review would happen under ideal circumstances:

You have a manuscript and it gets sent to reviewers who, between all of them, have deep expertise in your research, including in all or at least most of the methodologies you’ve used in your experiments. Some of them even do exactly the same kind of research you do, yet they feel no need to compete with you, so they are not overly critical. Also none of them are the type of person who gets an ego boost out of rejecting and eviscerating other people’s work. Instead, they are all very fair; just critical enough.

And despite the fact that they don’t gain anything from spending a lot of time on your manuscript, they pore over the paper, ask for the raw data, repeat any analyses you did, check all the references, and make detailed suggestions or corrections. If you did your analyses in a software they’re not familiar with, they reach out to someone who knows that software and ask them what they think. They make this effort simply because they care.

The reality

It’s not that I’m so cynical to think that reviewers never do a good job. But you almost never get close to this idealized kind of peer review. The reality is that you’re more likely to get reviewers who just don’t spend much time on the manuscript.

Then there’s bias, which could go in either direction. A reviewer could either be a competitor, or they could be someone who has some fealty to members of your research group, like your principal investigator (PI). If your PI is well-known in their field, or an editor at a journal that everyone in your field would like to publish in someday, that PI has some power to make other people’s careers difficult, which means reviewers might not want to piss him or her off.

In the worst case, a field may even be dominated by a research cartel, which could filter out any work that is against the consensus.

Who’s a peer?

Then there’s the issue of who is considered a “peer.” In many studies, a lot of different methodologies are used; that’s why there are often so many authors. Some of these methodologies are more finicky than others, meaning some are easier to screw up, sometimes in ways that significantly alter the results. These are cases where expertise in the methodology really helps. But you almost never get reviewers that, between all of them, are experts in all or even most of these methodologies.

Besides, reviewers are often not chosen because they are experts in the methodologies used. In fact, in some cases the writer of the manuscript has a say in who their reviewers are; they can request their own reviewers, in which case they might want to pick someone they know would go “easy” on them.

By the way, although it can certainly be helpful to have reviewers that do exactly the kind of research you do, this could also maintain a comfy bubble that leads to stagnation in a field. Sometimes it would be better to have someone in a different, or adjacent field; they can come up with interpretations that people in your field just aren’t aware of. That kind of thing never really happens in peer review though.

3. “Anecdotes are not data”

That brings me to the next argument frequently used by sophists and midwits; that “anecdotes are not data”. This is closely related to the previous claim about peer review, in that it highly favors certain types of evidence, namely those that are “officially sanctioned.”

Variations include:

That’s not “scientific evidence”

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard of evidence

There’s this misinformed notion that “anecdotes” are not “scientific evidence.” First of all, the term “scientific evidence” implies that some pieces of evidence are scientific and some are not. I would say all evidence is scientific, so it’s redundant to even say “scientific evidence.”

A problem with anecdotes is that they are often just a few data points, and they are not the result of controlled experiments. This causes some people to discount them altogether, and relatedly, claim that RCTs (randomized controlled trials) are the “gold standard of evidence.”

It’s true that it’s nice to have controlled experiments when possible, but that’s not always possible. It also ignores the flaws of RCTs, and the fact that RCTS are imminently gameable; just look at all the issues that this trial had.

Almost all types of evidence can have issues with it, but that doesn’t mean they’re not useful. That’s why ideally you’d have different types of evidence to support something.

And these can include anecdotes. Sure, it gets messy because you have to judge for yourself whether what you are seeing is just a coincidence, or something else. But no one said science was simple.

By the way, we intuitively know that anecdotes are useful. Otherwise, why would anyone care about how many years of experience a doctor has?

A good doctor who’s been in practice for many years has seen a lot of cases. So when they get a new one, they might have a good idea for how to treat it based on what they’ve seen before. They’ve become good pattern recognition machines. In other words, they’re relying on anecdotes that they’ve gathered over the years.

A simple example of when anecdotes can be useful

Suppose after a vaccination campaign for a certain virus, you anecdotally hear about severe negative reactions to the vaccines from several people in your social circle, despite the fact that you’ve been told over and over again that the vaccines are exceptionally safe. Sure, these are anecdotes, but if you’ve accumulated a handful of anecdotes, you should definitely be asking some questions. That’s just common sense. In other words, you don’t ignore this data.

Hopefully, in a sane society, when enough anecdotes like this have piled up, it’s used to generate hypotheses and fund some high quality studies, including RCTs to see if there’s something unsafe about the vaccines. And hopefully those studies are not unblinded prematurely, or run by the very makers of the vaccines, or run by third parties that have incentives to please the vaccine makers. Hopefully.

But if you suspect that you are not in such a society, you may have to weigh anecdotes more heavily than even some of the RCTs. In other words, the anecdotes are useful. The anecdotes are data.

A most interesting “anecdote” I came across in graduate school

I’ll also say that anecdotally, sometimes there is evidence that you hear about through word of mouth that never gets published into anything formal, and sometimes these happen to be some of the most interesting bits of information you come across during your graduate career.

Here’s an “anecdote” from my time in grad school, with everything anonymized because my goal is not to get people fired:

A post doc I knew conducted some experiments that showed that the data from one of his PI’s most important papers was the result of an artifact. By “artifact” I mean that the result was due to experimental error. Publishing these results would have been very bad for his PI (who was his boss). The post doc didn’t want to do anything to jeopardize his job, especially since it would mean losing his visa status. Long story short, the results never got published. For years afterwards, people conducted experiments on the assumption that the PI’s work was good, which wasted a lot of people’s time and money.

How often does this kind of thing happen? And how much worse is it when there’s big money, like Pharma money, involved?

4. “But it’s not statistically significant”

Variations include:

You didn’t do a statistical test

Goddamn p-values

Much of hypothesis testing in scientific papers, for better or for worse, uses frequentist statistics.

To illustrate: suppose we have a study that is testing whether a drug has a positive effect on a certain disease. By convention, we define a “null hypothesis” as the following: The drug has no effect. We want to know whether we should reject that null hypothesis or not. After we do our experiments testing the drug and placebo on some people, we come up with a result. At that point we’d usually use some stats software to calculate something called a “p-value.” The p-value answers the following question: what is the probability of seeing this result (or something more extreme) given that the null hypothesis is true? If that number, the p-value, is tiny, it means that the probability of seeing that result is tiny (if the null hypothesis were true). We therefore reject the null hypothesis.

The “cutoff” for what is considered “tiny” is usually set to 0.05. There’s nothing magical about this number. It’s just a somewhat arbitrary threshold that buckets results into “statistically significant” and “statistically not significant.”

A problem with this is that people often think that just because a result is not statistically significant, this “proves” the null hypothesis. So in our drug example, suppose we found that more people who got the drug showed improvement, but the results weren’t “statistically significant.” Because the results weren’t “statistically significant,” it might lead some misinformed researchers to conclude that the drug is of no use for the disease; in other words, the null hypothesis, which says that the drug has no effect, is true.

This is the wrong interpretation. This notion of “statistical significance” often leads scientists to deny differences that those uneducated in stats can plainly see. For more on that, read this article.

In a nutshell, there are many reasons why the drug may actually have an effect, but the results did not end up statistically significant. This may have to do with study design, or drug dosage or timing, or genetic differences between patients, etc.

The error can also go in the other direction; in other words, sometimes we can get a tiny p-value, but the drug actually has no effect.

This is why some people have called for an end to p-values, or at least to limit its use. At the very least, we should learn to embrace uncertainty, instead of “bucketing” results based on arbitrary cutoffs.

An anecdote about statistical significance that made me worried for the state of humanity

Several months ago I talked to a very well-credentialed doctor about the results of the Pfizer COVID vaccine trials. I told him that it was a red flag that more people died in the vaccinated group than in the unvaccinated group (for more on that see section 4 of this or read this). His response was that, well, the results weren’t statistically significant.

Really? That’s the response to the results? We’re told the Pfizer vaccines “save lives” and yet the one RCT with this vax actually showed all-cause mortality was higher in the vaccinated group, statistical significance be damned. Sure, we don’t know for certain whether all or any of those deaths were because of the vax. But doesn’t this fly in the face of “The vaccines save lives” trope? If those results were not a “red flag,” I don’t know what is.

“You didn’t run a statistical test”

You don’t always need to do a statistical test. Exhibit A:

That’s it for this section.

5. “Correlation does not equal causation”

This statement is, strictly speaking, true.

Of course correlation doesn’t equal causation. Of course just because we see a correlation between how much chocolate a nation eats and the number of Nobel Prizes it yields, that doesn’t mean that one causes the other.

But sophists and midwits take this argument too far. They abuse this argument and apply it to cases where there might actually be a causal link.

For example, someone might bring up the observation that, say, there was a rise in emergency cardiovascular events among the under-40 population in Israel in early 2021 during the vaccine rollout.

“Correlation does not equal causation” some might respond to this. How deep.

Except this isn’t like the chocolate-Nobel prize example. In this case we have other papers that link the vaccines to cardiac episodes (see here, here, and here). And we have plausible mechanisms of action (see section 5 here).

So although this statement is true, be careful when you hear it. The person saying it may have shut off their brain, and they might be trying to make you do the same.

6. “The truth is somewhere in the middle”

I hear this one from people who are actually very intelligent; people who are neither sophist nor midwit. It’s an easy one to fall for.

Occasionally reality does call for pants-on-fire panic

During the rise of Nazism, on the one extreme there were people ringing alarm bells early on, and at the other end there were people who supported the Nazis (this included several Nobel Prize winners and the majority of German doctors).

Some of the people ringing alarm bells might have looked crazy initially. This was before there was anything “obvious” going on; people weren’t being rounded up for concentration camps yet. So I could easily imagine that many people thought that yes, some of what was going on politically was not great but there was no need to panic. In other words, “the truth was somewhere in the middle.”

But who ended up being right?

Occasionally the person with the “extreme view” is right, and unfortunately, applying a simple rubric like taking the “middle” position will not reliably get you to the truth. Reality is just not that accommodating.

Pretending to be wise

This essay, on those who remain “in the middle,” is an interesting read. From the essay:

But trying to signal wisdom by refusing to make guesses—refusing to sum up evidence—refusing to pass judgment—refusing to take sides—staying above the fray and looking down with a lofty and condescending gaze—which is to say, signaling wisdom by saying and doing nothing—well, that I find particularly pretentious.

7. “You’re not qualified to [FILL IN THE BLANK]”

Last but not least, there’s the argument that just because you’re commenting on something that’s not “within your field” you should “shut up” because “you’re not qualified.”

This gets into what expertise is. There is too much to say here, so this will be in a separate article.

But for now, here are the variations and related phrases of this argument:

WHAT ARE YOUR CREDENTIALS

You haven’t published a paper in the relevant field

Stay in your lane

Trust the experts

Don’t do your own research

Don’t go down the rabbit hole

Have I missed any of the top abused arguments from sophists and midwits? If so, leave them in the comments below.

I love this substack. I have had all these thoughts over the past two years but could not articulate them as well. I have shared your posts with brainwashed people but alas, to no avail. Maybe because they’re midway sophists. They are also very pretentious, which seems to go hand in hand.

"A problem with anecdotes is that they are often just a few data points, and they are not the result of controlled experiments. This causes some people to discount them altogether, and relatedly, claim that RCTs (randomized controlled trials) are the “gold standard of evidence."

Funny thing is the same deep pocket corps who insist only RCT evidence has value also pay vast numbers of social media influencers because most ordinary individuals tend to put more weight on anecdotes related by a trusted individual.

Every playground has more useful information from other parents than official sources. For more than a decade doctors were surgically implanting tubes in the ears of kids with chronic ear infections and continued long after parents knew cutting dairy in the diets solved the problem.

Of course there are no sponsors for trials that make folks healthier w dietary balance.