How much should we worry about finding SARS-CoV-2 in the brain?

And what we can learn from plants

SARS-CoV-2 can be found in the brain

You may have seen media reports of SARS-CoV-2 virus being found in the brain:

These headlines sound scary. How worried should we be?

Let’s first briefly look at some of the studies these media articles base their headlines on.

Study 1

This study carried out autopsies of people who had died and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2: SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy

Most had severe cases of COVID.1 They got brain samples from 11 of the patients, and most had SARS-CoV-2 RNA in their brains.2

However, here’s something that’s strange:

Despite extensive distribution of SARS-CoV-2 RNA throughout the body, we observed little evidence of inflammation or direct viral cytopathology outside the respiratory tract.

And:

In the examination of 11 brains, we found few histopathologic changes, despite substantial viral burden.

By the way, you might be wondering, are they just detecting “dead” virus that isn’t able to infect and replicate in cells? Well, they found “replication competent” virus from one of the individuals. I assume that means they weren’t able to find viable virus in the brains of the other individuals.

Study 2

Now take this study, which performed autopsies on 17 patients who had died and tested positive for SARS-CoV-23: Unspecific post-mortem findings despite multiorgan viral spread in COVID-19 patients

They looked for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in multiple different organs like the lungs, heart, liver, brain, etc. They “found the virus in almost all the examined organs” but they didn’t find signs of inflammation or damage to the heart, liver, or brain.

They also mention:

As RT-PCR might just detect residual viral genome, it remains unclear whether this represents active viral replication into the tissues or previous cellular infection, without clinically relevant significance

In other words, we’re not sure whether the SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the organs is just “dead” virus or not.

Study 3

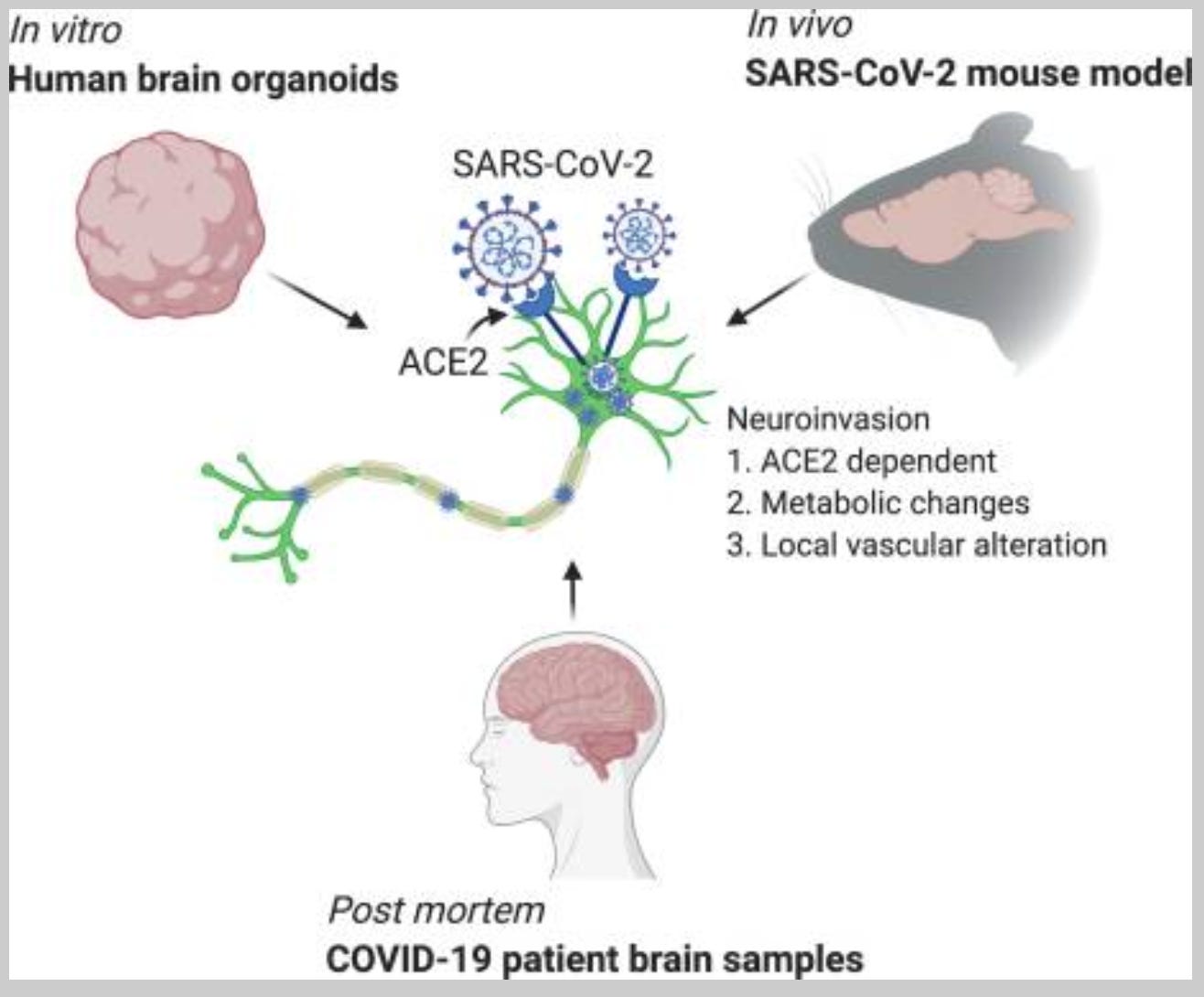

Next, let’s look at this: Neuroinvasion of SARS-CoV-2 in human and mouse brain

They found that SARS-CoV-2 could infect human brain organoids, which are tissue cultures that are supposed to mimic the brain. They also showed that SARS-CoV-2 could get into the brains of mice.4 Finally, in autopsies from three patients who died of COVID-19, they detected SARS-CoV-2 in their brains.

What do we see with other respiratory viruses?

The thing is, we’ve found evidence of other respiratory viruses doing similar things. And I don’t just mean exotic respiratory viruses, but mundane ones that cause the common cold or flu.

For example, there’s this study from 1997: Infection of primary cultures of human neural cells by human coronaviruses 229E and OC43

They found that coronavirus strains 229E and OC43, which cause the common cold, could infect human neural cell cultures.

This study found these same strains in the brains of people: Neuroinvasion by Human Respiratory Coronaviruses

They looked at brains from donors who’d had neurological diseases, as well as normal controls. Here’s what they found:

“MS” stands for multiple sclerosis and “OND” stands for “other neurological diseases.”

We don’t just find these coronavirus strains in the brains of people who’d had MS or other neurological diseases. In fact, the normal healthy people had a higher incidence of both strains compared to the “other neurological diseases” group! Again, these strains cause the common cold.

There are other papers like this, showing “neuroinvasion” from coronaviruses, influenzas, and other respiratory viruses:

Differential susceptibility of cultured neural cells to the human coronavirus OC43

Acute and Persistent Infection of Human Neural Cell Lines by Human Coronavirus OC43

Human Respiratory Coronavirus OC43: Genetic Stability and Neuroinvasion

Evidence for Influenza Virus CNS Invasion Along the Olfactory Route in an Immunocompromised Infant

Experimental influenza causes a non-permissive viral infection of brain, liver and muscle

Rhinovirus infection in neuronal cells and brain

That’s just a random sampling of papers.

Now, I’m not saying that having these viruses in the brain is harmless. But if we’re going to panic about SARS-CoV-2 in the brain, why aren’t we panicking about these other respiratory viruses, which can also be found in the brain?

I guess we think of those viruses as more harmless than SARS-CoV-2. But is that rational? I don’t think we know whether SARS-CoV-2 “neuroinvasion” happens more frequently than “neuroinvasion” from other respiratory viruses. And yet the media makes us think that SARS-CoV-2 is particularly bad in this regard.

But COVID-19 can lead to neurological symptoms

But, you might say, COVID-19 can lead to neurological symptoms in some people. That’s true, and so can other respiratory viruses, including ones that cause the common cold or flu:

Human Coronavirus OC43 Associated with Fatal Encephalitis

Influenza B Virus Encephalitis

The hidden burden of influenza: A review of the extra-pulmonary complications of influenza infection

Encephalopathy associated with influenza A

A severe case of human rhinovirus A45 with central nervous system involvement and viral sepsis

Neurologic Alterations Due to Respiratory Virus Infections

Neurologic Complications Associated With Respiratory Syncytial Virus

Extrapulmonary manifestations of severe respiratory syncytial virus infection – a systematic review

Respiratory syncytial virus infection and neurologic abnormalities: retrospective cohort study

Again, what is the rate at which neurological complications occur from SARS-CoV-2 and how do they compare to the rates we see from seasonal respiratory viruses like the common cold or flu? And are the neurological complications from SARS-CoV-2 worse than what we see with these other viruses?

If we’re going to fearmonger, shouldn’t we be fearmongering about those other viruses too, for consistency’s sake?

Neurological symptoms don’t correlate that well with SARS-CoV-2 in the brain

Here’s another puzzle: SARS-CoV-2 in the brain doesn’t correlate neatly with neurological symptoms or signs of brain inflammation.

Recall that in the first two studies mentioned earlier they had found SARS-CoV-2 in the brain, but no evidence of brain pathology or inflammation, as far as they could tell. Now, maybe there was some damage to the brain but it was too subtle to be measured; we can’t rule that out. However, this is the data we have to work with.

Then there’s this study: Dysregulation of brain and choroid plexus cell types in severe COVID-19

That study looked at people who had died with COVID-19, whose brains had signs of inflammation and dysregulation. None of those patients had any traces of SARS-CoV-2 in the brain however.

Here’s another study: Neurovascular injury with complement activation and inflammation in COVID-19

The patients in that study also died with COVID. They exhibited all kinds of brain pathologies, but:

We used multiple techniques to detect SARS-CoV-2 in the brain… All techniques failed to detect any virus in the brain, including regions where there were obvious signs of inflammation

Here’s another one: Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series

This study looked at the brains of patients who’d died and tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. Here’s what they reported:

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the CNS was not associated with the severity of neuropathological changes.

“CNS” stands for “central nervous system,” which includes the brain and spinal cord.

So neurological symptoms are frequently decoupled from the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the brain.

That’s not to say that SARS-CoV-2 virus in the brain will never directly cause brain damage or neurological symptoms; I expect that sometimes it will.

But again, recall that common cold strains were found in brains from healthy donors. Is it possible that virus in the brain is actually neutral sometimes? Perhaps they only become a problem in people that are genetically susceptible or weakened somehow? Or are we looking at latent viruses that could potentially cause issues down the road?

What we can learn from plant biology

It might be useful to shift out attention to plant biology. It was already recognized a century ago5 that healthy plant tissues contain abundant microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and viruses. These organisms are called “endophytes”; they’re microbes that reside within the tissues or cells of living plants without causing any overt negative effects.6

Plant biologists now recognize that some plant viruses can have neutral, or even positive effects on the plant.

According to this study, infection with Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) improved drought tolerance in several plant species and enhanced freezing tolerance in beet plants.

Then there is this fascinating paper: A Virus in a Fungus in a Plant: Three-Way Symbiosis Required for Thermal Tolerance

Apparently there’s a fungus that lives in a plant, and this fungus confers heat tolerance to the plant, but only if the fungus is infected by a certain virus. If the fungus is cured of the virus, the heat tolerance, in both the fungus and plant, is lost. Who woulda thought!?

Maybe the biologists studying humans haven’t quite caught up with what’s been known in plant biology. If plants have neutral or even beneficial viruses in their tissues, isn’t it conceivable that we would too?

Maybe, like plants, our bodies are just not as sterile as we thought, and the presence of virus alone is not sufficient to cause damage. For more on that, see this review.

I'm not saying that having SARS-CoV-2 in one's organs is a good thing; it’s probably not. But the fact that there are so many puzzles in human virology, like the fact that there are common cold strains in the brains of healthy humans, might be an indicator that the field could use some outside ideas.

By the way, this wouldn’t be the first time that research in plants could contribute to another field in biology. What we know about Mendelian genetics came from work done in pea plants, and the discovery of jumping genes (transposons) came from research done in maize. That’s why it’s important for fields to branch out of their narrow scope of vision.

SARS-CoV-2 in the brain needs to be put into context

It’s not that we shouldn’t be worried about SARS-CoV-2 being in the brain, but the finding should be put into context.

We know that other respiratory viruses, including those of the common cold, can also be found in the brain, including the brains of people without any known neurological issues.

We know that in plants there are all kinds of microbes or viruses that reside within their tissues, but don’t seem to cause harm.

We know that neurological symptoms don’t correlate neatly with the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the brain.

We also don’t have brain samples from healthy people who recovered from SARS-CoV-2. How often is SARS-CoV-2 found in those brains? And even if it turned out that it was often, what would that mean?

It makes sense to be concerned about SARS-CoV-2 being found in the brain; after all, there are a lot of unknowns. But putting the findings into context paints a different picture from what we see in the media.

Although two had mild or no respiratory symptoms and had died with, not from, COVID-19. One of those cases was a juvenile with an underlying neurological condition.

In one case, they even found SARS-CoV-2 RNA as late as 230 days following symptom onset.

By the way, we can’t rule out the possibility that in some of these autopsy cases the people were either falsely diagnosed with COVID, or had died with COVID, but not necessarily of COVID. However, for the purposes of this article we can take their results at face value.

The mice overexpressed human ACE2 (a receptor that the virus needs to get into cells).

This appears to have first been discovered in 1923. According to this paper, An Endotropic Fungus in the Coniferæ, the possible presence of a fungus in living plant tissue “seemed so unlikely that the matter was not then further pursued." But luckily it was eventually brought to light again.

The fact that microbes could live within tissues, or even within cells, could actually have been predicted given what we know about our evolutionary history. Eukaryotes, which include animals, plants, fungi, and lots of single celled organisms, derived from a cell that engulfed a bacterium at some point. That engulfed bacterium would later lose its independence and become “enslaved” as an organelle in the cell, and become what we now know as the mitochondrion, which is responsible for some key metabolic reactions in eukaryotic cells related to getting usable energy from food. The fact that this happened means that there was a period of time when the engulfed bacterium was living in another cell. If that was happening back then, why wouldn’t it be happening now?

Moreover, this has happened multiple times in evolutionary history. Plants and algae have chloroplasts, which is the site of photosynthesis, and these were also derived originally from cyanobacteria (a type of photosynthetic bacteria) that had been engulfed. Various different unicellular eukaryotes have engulfed other eukaryotes as well, multiple times in history (more here).

Then we also have evidence for pieces of virus genomes having integrated into the genomes of their hosts. That seems to suggest that the virus hung around in host cells long enough without causing overt negative consequences; after all the host cells survived into the present day.

Darn, Joomi!

I've been thinking of writing a series on viral parkinsonism after your case report on the septuagenarian with pre-diagnosed Parkinson's being exacerbated by the vaccines but shelved that. It appears you were able to get to many of those points! Ironically, I'm also looking a bit at the microbiome in my recent posts, so maybe hold off before you dive deeper into that first! 😉

There's a lot going on right now that seems very scary, but under many circumstances the fear can override rational thought. If context is removed then it's easy to see things from only one perspective.

Many things would need to be looked deeper, and we do need to find answers but we also require a lot of context when examining information.

Never discount neurotoxicity from the GP120 inserts in S1, that easily crosses the blood brain barrier and doesn't require live virus.

It can persist in the axon for decades and inhibit neuron function without killing it.

I will update this review in the next couple of days with a contents and new research:

Pathophysiology of "brain fog"

https://doorlesscarp953.substack.com/p/pathophysiology-of-spike-protein